The end of the Pom Mahakan community – an almost 2-century-old settlement - reflects the ignorance of the Bangkok administration and Thai society about preserving the history of normal townsfolk, especially when the Thai-style costume trend is on the rise.

I have covered the story of the Pom Mahakan community as a journalist for the past year. The community population had already shrunk from 300 to around 50 people. No more than 15 houses were left intact.

Thawatchai Woramahakun, a former community leader, prostrates himself in thanks for support to the community for the past 26 years in combating eviction

However, the remaining houses behind the Mahakan fort still told the stories of the past through their architecture, the textual descriptions displayed by the community and their decrepit structure.

The 26-year journey in opposing the eviction plan imposed by the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) involved many outside individuals and organizations. The community that was established during the reign of the King Rama III finally proved its value and changed from an infamous hub for drugs and fireworks to a living historic community.

Unlike the state- and palace-centric history of schoolbooks, Pom Mahakan community’s history and value lies in its tradition, history, community structure and architecture. Each old house has its own story to tell.

In the end, the fort wall and house doors were not able to resist the pressure of the BMA. To be exact, the community never had the upper hand in pushing its transformation into a ‘living museum’ in which the community would still live there and participate in protecting the fort and its wall, which are registered as an archaeological site.

House number 99, a signature community landmark which was listed for preservation but torn down anyway.

There are two reasons that support my statement above. First, the resolution of the four-party negotiations, consisting of the BMA, civil society, the military and the community, collectively decided to conserve only houses that bear the so-called “five values dimension”; historical, artistic, architectural, social and archaeological and academic values.

However, the only thing that would be kept were the houses. The residents would still be required to leave. In my opinion, the community strategy was to basically agree and then push their agenda further later on. As a result, the owners of houses that would be demolished were automatically separated from those whose houses would be left intact.

The separation caused conflict within the old community. The solidarity was further cracked after ISOC, the quasi civilian-military unit that is in charge of domestic security — a term that is interpreted very widely — deployed their men in the community.

ISOC claimed they were there to enforce the order of the junta leader in abolishing the fireworks business even though the community confirmed that it had already disappeared.

One more reason for the ISOC adventure into the community was to abolish the local mafia, in other words, the community leadership. This issue is twofold. Some people who moved out said they were threatened by the community leadership. Those who would not leave said that ISOC was the one causing the internal conflict that went far beyond repair.

Secondly, according to the resolution from the four-party panel, the option on the table that was considered as involving most of the stakeholders was rejected by this BMA administration. The houses that were on the conservation list were brought down to the ground one after another. The idea of transforming the community into a living museum was abandoned.

Two reasons reflect that the community goal to sustain their space has never been accepted by the BMA authority. Even though there was a glimmer of hope during the Apirak Kosayodhin administration, it did not last long.

Here is my question on the appropriateness of ISOC’s adventure into the community: Given that the Bangkok governor sits as the local ISOC director, what is the reason for using a civilian-military unit to take care of civilian matters?

Moreover, the ISOC officers quickly moved out after all the community decided to leave, so what exactly was the reason for ISOC? Were they involved in the community conflict? Were community people affected by their ‘divide and conquer’ tactic? ISOC has to step up to clear the doubts.

Community members who moved out, in fact, received compensation of around 10,000 to 100,000 baht. However, this was not enough for them to resettle on new land which costs more than 3 million baht, even though they spent all of their compensation and their collective savings that came to 100,000 baht.

Their relocation costs (land and buildings) was not used to calculate their compensation. Moreover, their living costs are on the rise as they live further from their workplaces and schools.

A demolished house

Michael Herzfeld, professor of anthropology from Harvard University, was one of the first westerners to research the Pom Mahakan community. He told me that there is an example of a community that preserved their old town in Rathemnos, Greece. The Greek government also supported them in keeping their 400-year-old houses as a tourist attraction.

Rathemnos is now quite a popular tourist attraction. Community members earn money as they use their houses to host tourists. As a result, they did not suffer much during the last major economic crisis.

There are many examples of historic community preservation around the world. I started to wonder; is it too modern for Thailand to adopt that mindset?

The idea of replacing the community with a public park started in 1959. The evictions started in 1992 and have continued until today. That means that the BMA’s antiquated conservation mindset has remained unchanged for 59 years.

The thick fort wall and canal that surrounds the area will make the park a good shady place for criminals. One of the community members told me that there had been a couple of robberies. There was also an outsider who committed suicide by hanging himself.

The community members had proposed helping the BMA to keep watch in the park if they were allowed to live there. Of course, it was rejected. The park construction is in progress. And do not forget that it will be built by driving 300 people from their homes.

An entrance gate of Pom Mahakan

‘Gentrification’ is the word that really well describes the action of the state against the Pom Mahakan community. A small group of people decided how one space should function without listening to the stakeholders.

On the other hand, community members with outsiders successfully identified their own community values by their way of life ( what is called ‘self-gentrification’). The Pom Mahakan community stood as a landmark of a self-transforming community. Its residents determined the community’s values and they interacted with each other really well. All of this happened in the age where Bangkok people are reluctant to say hi to their neighbours.

The fall of the Pom Mahakan community underlines the state’s almost 60 years of ignorance yearning for beautiful public parks regardless of residents. It lacks understanding about the space, the community and the idea that allows people to live and at the same time conserve an archaeological site.

The BMA action on the Pom Mahakan community is a textbook example of outdated administration. Moreover, it has taken place in Thailand’s capital city.

It is even more paradoxical that the eviction was enforced amid a history conservation trend where Thai people have taken a fancy to cosplaying in traditional Thai costumes, in imitation of the characters in the popular soap “Love Destiny.”

Tearing a community apart is an irreversible process in terms of physical and psychological space. It is also the eradication of the history of normal people in Bangkok. There are many other communities similar to Pom Mahakan. Where is the next domino for the BMA?

This is a time when people prefer cosplaying as Thais of a romanticized bygone era to preserving real history.

At this time the state evicts people from their homes by physical harassment and threats to burn their houses to ashes (in the case of Kaeng Krachan) without any perception that humans can actually live in harmony within the forest and history.

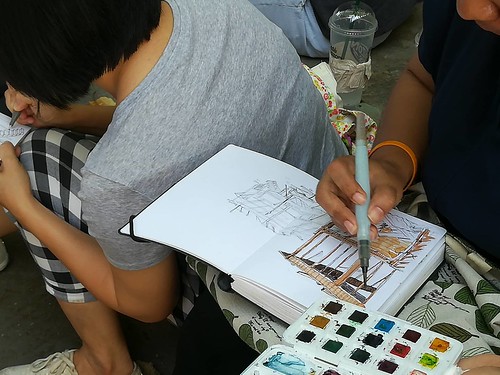

The Bangkok Sketchers, a sketching enthusiasts group, come to sketch the fort community before it vanishes. One group member said they were so sad the community was being evicted.