Although the Constitution supposedly guarantees the right to bail, it is as if that right does not exist for a lèse majesté suspect. In the case of Jatupat “Pai” Boonpattararaksa, the court seemed to improvise the reason for revoking bail beyond what the law allows, an expert says.

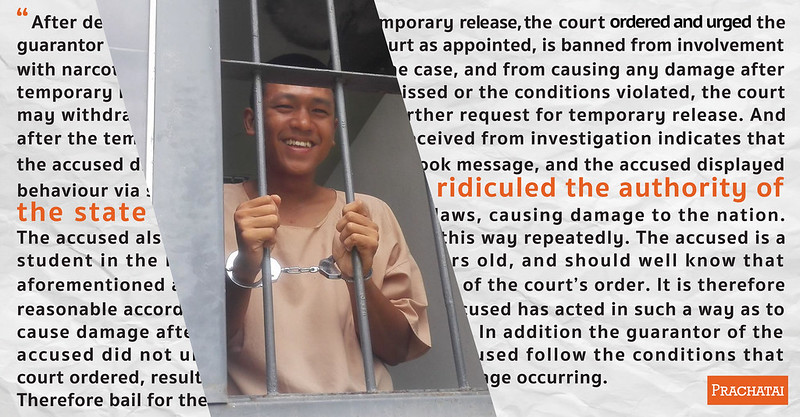

21 December 2017: Jatupat “Pai” Boonpattararaksa wore his graduation gown over his Department of Corrections-issued prison uniform, amid his loved ones and supporters, before he testified at the military court at Sripatcharin Camp at the 23rd Royal Army Base in another case where he was charged with holding an activity, “Speaking for Freedom”. This is one of the five cases he has faced since the coup in 2014.

Other than his loved ones and political comrades, a group of children on their way to a music contest thanked Pai for teaching them how to play the phin and khaen. Before they left, they took a photo with the still-smiling Pai.

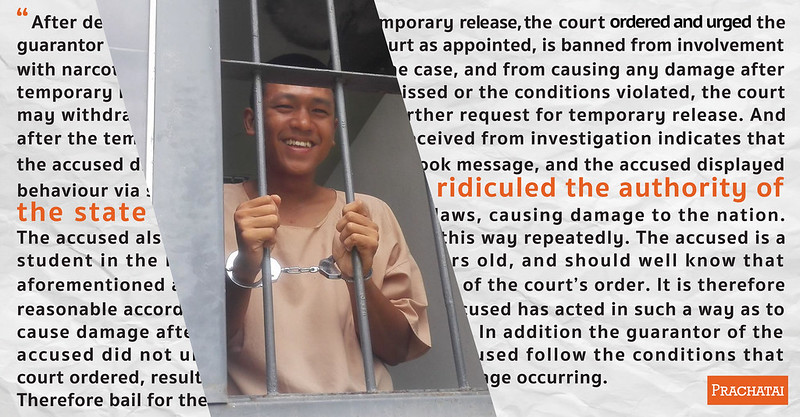

On Dec. 22, 2016, just over a year ago, Jatupat “Pai” Boonpattararaksa, a law student at Khon Kaen University, answered a court summons at Khon Kaen Provincial Court. Police investigators had petitioned the court to cancel bail on his lèse majesté case, citing the reason that Pai had “mocked the investigators”. The court deliberated the investigator’s petition and ruled that:

“The accused did not delete his Facebook message with which he is charged in this case, and the accused displayed behaviour via social media in a manner which ridiculed the authority of the state without fear of the nation’s laws, causing damage to the nation. The accused also had a tendency of acting in this way repeatedly. The accused is a student in the Faculty of Law and is 25 years old, and should well know that aforementioned actions constituted a violation of the court’s order. It is therefore reasonable according to the petition that the accused has acted in such a way as to cause damage after being temporarily released. In addition, the guarantor of the accused did not urge or take care that the accused follow the conditions that court ordered, resulting in the aforementioned damage occurring. Therefore bail for the accused is revoked.”

Jatupat celebrates his graduation with his parents in front of the court building

The case was filed by Lt. Col. Pitakpol Chusri, a military officer in charge of overseeing political movements in Khon Kaen. He gave evidence that Pai shared a BBC Thai biography of Rama X—an article that 2,800 others also shared.

After that day, the court never again granted bail to Pai although he submitted dozens of bail requests. Each time, the court gave the reason on that there was “no reason to change the former ruling.” Finally, Pai confessed that he shared the alleged Facebook post, but did not admit that what he had done was illegal. On August 15, 2017, the court sentenced him to five years in prison but halved it due to his confession, for a total of 2 years and 6 months. At that time, Pai had already been in prison for 244 days.

“Ridiculed the authority of the state:” An unprecedented condition for revoking bail

Sawatree Suksri, Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Law at Thammasat University, said in a seminar “When the Right to Bail Disappears” on 15 January 2017 that in principle, the alleged offender in a case should be treated as innocent until proven guilty, and the authorities cannot treat suspects as if they were already guilty, but act on the hypothesis that they are innocent. Therefore, denying temporary release goes against this principle and basic human rights. Exceptions must be meticulously decided, with clear reasons, on a case-by-case basis.

There are three main types of temporary release on bail, said Sawatree. The first is release without conditions. In the second type, the suspect promises to show up to court as scheduled or according to a court summons. If they do not show up, then they will be fined. The third type requires bail money as a guarantee. If the suspect does not show up in court as scheduled, the court will confiscate the bail money.

The court can use their discretion to release the alleged offender without conditions if their behavior does not pose any problems. However, in almost all cases, the court demands a guarantee, showing the discrimination inherent in the justice system. While release with conditions but without a guarantee is practiced in foreign countries, in Thailand the opposite is practiced. In Pai’s case, during his first temporary release he put up a guarantee, but the court also issued conditions for his release. Sawatree insisted that Pai did not violate the bail conditions.

As for the court’s determination that Pai was challenging the state’s power, Sawatree said whether or not Pai intended to “ridicule the authority of the state” is supposedly irrelevant to determining his freedom. First of all, ridiculing the authority of the state does not constitute a violation of the bail conditions. Secondly, since the sovereignty of the state is owned by the people, the government is merely the representative of the citizens. Therefore, mocking or challenging the state’s authority is basically a citizen mocking their own authority.

Of course, the court can use their discretion but they must use it within the framework of the law, rather than completely improvise. The revocation of Pai’s bail, Sawatree said, may not be within the law.

“If we say that this country is still a democracy, power belongs to the citizens. The question is: how is it wrong if citizens mock themselves?” she said.

When bail is revoked and you can’t fight your own case, then you’re forced to confess.

“In terms of feeling, I don’t feel anything anymore. Being denied bail has become a normal thing after something like this happens. If you were to compare it to a boxing match, I lost even before getting in the ring. But I’ll still fight though I know I’ll lose because I think it’s the loser’s victory.” —Pai Dao Din, Jan. 1, 2017

“After the 2009 coup, the justice process—especially for 112 cases—has been a coercive process that forces people into corners, forcing them to choose between confessing and fighting the charges...even though you believe you’re innocent, but nothing is certain because nowadays, the interpretations push the envelope more and more...If you fight, you’ll be locked up. If you lose, you’ll be locked up for longer. That’s the nature of 112 cases. Finally, people confess in droves.” —Sawatree Suksri, 19 January 2017

Although the Constitution states the right to bail as well as the assumption that alleged offenders are innocent until proven guilty, these rights are not exercised in lèse majesté cases. iLaw, or the Freedom of Expression Documentation Center, has stated that since the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO)’s coup on 22 May 2014 until15 January 2017, there have been 73 cases of lèse majesté. Of the 46 requests for bail, only 18 were granted.

Sawatree stated in her seminar on “Judgements and Rights to Temporary Bail in 112 Cases” on 19 January 2017 at Thammasat University that being denied the right to bail in lèse majesté cases is a method to force defendants to confess. Being held behind bars devastates one’s mental condition and prevents one from fighting the case by finding evidence and witnesses. Worse, defendants are not allowed to consult with their lawyers in private although this is a legally-sanctioned right. In lèse majesté cases, the court often holds secret proceedings, with only the defendants and their lawyers present. These conditions, said Sawatree, are authoritarian, forceful, and instill fear.

“For many years Thai courts have regularly refused bail to people awaiting trial for ‘insulting the monarchy,’” Adams said. “The systematic denial of bail for lese majeste suspects seems intended to punish them before they even go to trial.” —Brad Adams, Asia director at Human Rights Watch, 20 August 2014.

The article is originally written in Thai and available here.