Survivors of the massacre seven years ago of red-shirt protesters by the Thai government are sharing their memories under the hashtag #10AprilWhereAreYou. With no state or military officials ever prosecuted for their role in the political violence that took more than 90 lives in April-May 2010, the stories aim to keep alive memories of those who died and of the state’s role in those civilian casualties.

Here, Prachatai has collected three poignant homages to those who sacrificed their lives for political change posted on social media under #10AprilWhereAreYou. Find more information here on the April 2010 crackdown.

“I cannot forget”, Noppakow Kongsuwan

Have seven years passed already? Why does it feel as if it has been a much shorter time …?

‘Today is 10 April,' my mobile calendar tells me, which I then repeat to myself.

I write about 10 April every year. Some people are probably bored of it — after all, 7 years have passed and nothing has changed. Those who committed murder in the middle of the capital city act as if nothing ever happened, washing their bloody hands clean.

Some pragmatically hide the spots of blood that stain their hands and have even become influential and well-known.

Today, seven years ago…

Some people were perhaps preparing to return home for Songkran.

Some people were perhaps with their significant other.

Some people were perhaps at lunch, shopping, preparing to travel over the long weekend.

Some people were perhaps wondering why, today, there were so many soldiers out and about. Why is the traffic so clogged? Why are people wearing red?

Some people were perhaps watching the news on TV, wondering why, today, everything is chaotic.

Some people were perhaps also feeling that those creating the disorder deserved to die. Then, this country could have peace.

Some people that day were perhaps not interested, apathetic, because they do not find politics personally relevant, and do not like disorder.

Some people, now, perhaps are asking what happened? What is the truth?

Some people perhaps have forgotten that day completely, and wonder where they were that day, what they thought, what they did.

But many people that day, on Ratchadamnoen Avenue on 10 April 2010, met only one fate …

Many people that day left their homes for Ratchadamnoen Avenue.

Many people that day decided to join the red shirt movement for the first time, without caring for what their friends and onlookers would think.

Many people that day walked from Ratchaprasong Intersection to Ratchadamnoen Avenue.

Many people that day sat with only their bare hands, and faced tanks and battalions of soldiers.

Many people that day choked on tear gas that fell from helicopters.

Many people that day fought fully armed soldiers with their bare hands.

Many people that day dodged bullets, hiding between buildings and trees.

Many people that day used wooden sticks to fight bullets and guns, and pried bricks from the ground to protect themselves from the bullets that flew through the air.

Older uncles and aunties that day threw fresh food, vegetables, threw whatever they could to counter the soldiers who fired bullets, to make the soldiers stop shooting.

Some children that day had tear gas fired at them until they were blind, blind on Ratchadamnoen Avenue.

Many people that day were wounded from the shooting. Some lost arms and legs.

Many villagers lost their lives that day, shot with high-velocity bullets from guns positioned in the buildings above.

A Japanese journalist was shot dead, merely for taking photos of soldiers shooting citizens.

Villagers holding the Thai flag, wearing red shirts, were shot dead, their brains scattered across Ratchadamnoen.

I saw people die. I saw blood flow. I saw death right there.

I saw people carrying bodies and placing corpses on the stage at Ratchadamnoen. Corpses and corpses, waiting to be moved.

I saw relatives of the dead, crying and crying as if they themselves were about to die. They ran to declare themselves on stage as relatives of the dead, and to ask to see their faces one last time. But it was such a long way to run, and some had not worn shoes since leaving their homes.

What became of that day’s atmosphere? All that remains is the smell of death, bullet marks and blood marks, tear stains. There is only anger and loss.

Those who died, those who were injured, they came merely to ask for democracy, for parliament to be dissolved. They came to ask for ballot boxes but returned with coffins and corpses.

Some people perhaps have already forgotten 10 April, what happened and what it was.

Some people perhaps remember only some, and have forgotten some. Some people are okay with that.

Some people perhaps would perhaps like to forget it all.

Never mind. To not remember, to forget it all, that is your choice.

But I probably will not be able to forget.

Will not be able to forget who died, death, pools of blood, tears and loss.

Even if people order us to forget, our subconscious replies immediately ‘I can’t forget’.

And if not forgetting, speaking about 10 April, requires sacrifice — we must sacrifice all that it takes.

Whatever it takes to not forget, to continue speaking.

Noppakow Kongsuwan

Ratchadamnoen

10 April 2017.

“Dirt fighters, anonymous forever” Chetawan Thuaprakhon

So we return to seven years ago, the day the government committed heinous crimes.

Back then, Phi Bird and I were still field journalists chasing scoops on the ground most of the time. And there was no news in 2010 larger than the United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship protests, or the ‘red shirts’ as they are popularly called.

On 10 April 2010, we were on duty together, and were deciding who would be positioned at the protest stages at Ratchaprasong Intersection and Saphan Phanfa respectively.

“I don’t mind where I go,” I told Phi Bird. In the end, Phi Bird chose Saphan Phanfa, perhaps thinking me a country boy who should have the opportunity to visit the Ratchaprasong business area.

Around 10 AM, Ratchaprasong began to hum with rumours about a ‘government crackdown’ at both areas. The protest leaders were clearly restless after a government press conference at 11 AM; they rushed to make calls to confirm the news that guards behind the stage were beginning to amass.

“The government will crackdown on both areas … Ratchaprasong first … Saphan Phanfa first,” and on and on. The leaders were agitated, sure of little — but sure also of the sounds of explosions, that with each boom forced all to prepare escape routes.

The UDD guards began to hand a piece of cloth and a bottle of water to each protester and journalist for relief in the event of tear gas. I took a mask, water in my rucksack and tied my shoelaces tightly. I was ready to run to wherever news broke.

For a long time, both Ratchaprasong and Phan Fa Lilat buzzed with rumours that soldiers had been ordered to ‘take back the territory’.

“How is it over there?” I phoned Phi Bird, “Do you need any backup? Nothing much is happening here.”

“Soldiers have arrived, but it’s alright so far. The situation is stable,” Phi Bird replied.

I sat monitoring news of the military’s movements at Saphan Phanfa. Protest leaders sporadically gave speeches and updates on the Ratchaprasong stage. Sometimes they called for re-enforcements.

“How is going?” I phoned Phi Bird again.

“It’s bad. Someone has died already. It’s extremely chaotic. Tear gas is clouding everything. That’s all for now. If anything happens, I’ll call you,” Phi Bird answered. The sounds of guns and bombs sporadically going off came from the other end of the line.

Late afternoon came. A UDD leader announced on stage that, “Somebody has died at Saphan Phanfa.”

The sounds of curses and anger. Some people cried, their eyes vividly red. After the first corpse, UDD leaders announced the deaths of a second, a third, a fourth, a fifth, a sixth and on and on, as if it would never end. After all, the deaths had come from high-velocity bullets.

Before sunset, Phi Bird called to say that the UDD leaders had announced the closure of the Saphan Phanfa protest area, and encouraged protesters to move to Ratchaprasong. Nattawut Saikua, a leader at Ratchaprasong, called on everyone to assist their friends and kin in shifting base to Ratchaprasong, which was to be the only remaining protest hub.

So, the closing of Phan Fa Lilat. But clashes between protesters and soldiers, and the escalating death count were to continue.

“Day and night passes, dissolving, fading. All is burnt to ash. Are there people braver than this? Ready to die together until the last,” sang Chin Kammachon, who was on stage singing “Dirt Fighters’.

Together, the tears of so many protesters at Ratchaprasong flowed. “Dirt fighters, anonymous forever. This utter ash will change destiny.”

The song finished. Sounds of people cursing the actions of the authorities. Some protesters from Phan Fa Lilat recounted the draconian events they saw.

Throughout the day and evening of 10 April, Saphan Phanfa, Ratchadamnoen and Khok Wua Junction become barren war zones.

The next day, vestiges of violence: bullets wedged in walls, electricity poles, cars. The flesh, blood and spirit of the people who came out to protest with two bare hands — to demand that a government that did not come from an election dissolve parliament, and return power to the people.

#10AprilWhereAreYou

“I didn’t feel so different from them”, Wirapa Angkoon

Where were you on 10 April 2010?

I was at Saphan Phanfa. I had just made a deadline the day the government announced that it would crack down seriously on the protesters. The sound of helicopters circling filled the air all day. That day, all I felt was that I had to go, to be an eyewitness.

I was not protesting with the red shirts but I felt I had been among them for a long time. Working in my office, I heard their speeches every day. A red flag still marked the protest area. In the evening, I should drop by on the way home to admire developments. I didn’t feel so different from them.

At about 3 pm 10 April, a pal and I were passing through Phra Sumen Road. What I saw made my hair stand on end. A line of tanks had already sealed off Saphan Wan Chat Intersection. There are no cars; but troops and people.

Then two or three red shirts came and sat in the middle of the road. They shouted that they were unarmed, please don’t shoot, please don’t hurt anybody.

The sun is searing. A street vendor gives the red shirts some paper to sit on. Upon seeing that they were red shirts, she piled some wood around them for shelter. A journalist runs over. The soldiers say that unauthorised parties must leave the area.

I skirt the edge of a crowd in front of Satriwithaya School, unaware that over the next few hours people would lose their lives in that exact place. I continue on until I am out of Ratchadamnoen. People are looking up at the sky, saying that helicopters will shoot down at them, and that they will not miss.

A screeching sound thunders above us; it is the first release of tear gas. The nearby Bangkok Bank is shrouded in smoke. People sitting nearby flee in panic; we run too. Somebody tell us to cover our mouths and noses. Somebody hands us a bottle of water to splash our eyes. In that moment, I am filled with anger.

No buses ran that night, so I rode a ferry home, the same time that red shirt numbers at Ratchaprasong and Khok Wua began to escalate. I could only pray that that nothing would happen that night. But as soon as I arrived home, I heard news of the first casualty, and then a second and a third followed. Since that second, I have never forgotten that ‘here, people died’.

We share these memories, so that “at the very least we can remember that we were there that day, that day that people died”.

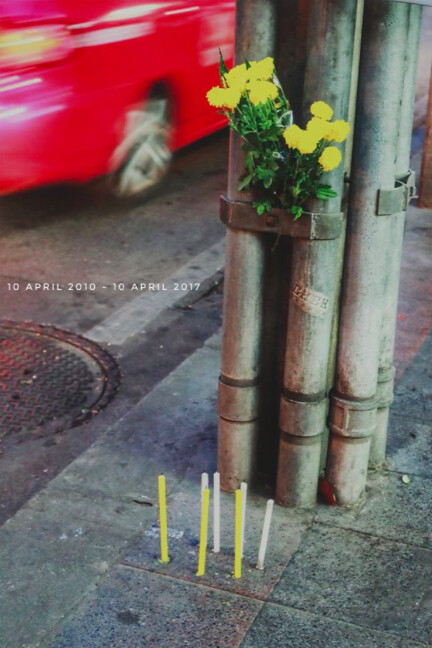

Note: All photos were provided by Noppakow Kongsuwan. Permission for stories to be translated and published was given by all parties.