In the final part of the Modern Thai Student Movement paper, the authors explored the aspirations of two more students activist bodies from Isan who harness their energy in amending Thai educational systems. One group comprises future teachers who try to create the culture of ‘lifelong learning’ and independent thinking, while the other encourage fellow students engage in activities outside the university gates.

After tanks and military boots were deployed on the streets of Bangkok on 22 May to stage another coup d’état not even a decade after the 2006 coup, many anti-coup political dissidents flocked to the streets to protest against the new military regime. With the subsequent imposition of martial law however, the voices of these political dissidents eventually died down after months of arbitrary arrests and detention.

Nonetheless, it has become clearer that the new military regime’s reform policies and proposed bills on various issues, such as education, energy, natural resources, land reform, forestry, immigration, education and tax, will benefit some groups of people while negatively affecting others. NGOs and political activists have begun to challenge the junta once again despite the imposition of the martial law, which gives the regime unprecedented power to make arrests over any expression of anti-coup opinion. In November, five student activists from the Dao Din group of Khon Kaen University in the Northeast, gave the three-fingered salute to Gen Prayut Chan-o-cha, the junta leader. The students were immediately detained and later interrogated by the military. The military also involved their parents and threatened to have them fired from the university if they did not accept the junta’s conditions. Although the junta might expect the harsh treatment and intimidation of the Khon Kaen students to serve as a lesson to keep other young activists at bay, the result was the opposite.

One after another, despite the presumption that the era of Thai student movement ended with the bloody student massacre of October 1976, student activists of various political orientations began once again to voice opposition to the suppression by the junta. Although these new student movements are not mass youth movements affiliated with political ideologies as in the 1970s, neither are they affiliated with the current colour-coded political divide in Thailand. These young activists began to engage in many regional and national problems despite the obstacle of the martial law. To look into the history, dreams, and aspirations of these student activists, who are now at the forefront of Thailand’s political mobilization, Prachatai introduces the series “The Modern Student Movement,” by Emma Arnold and Apisra Srivanich-Raper.

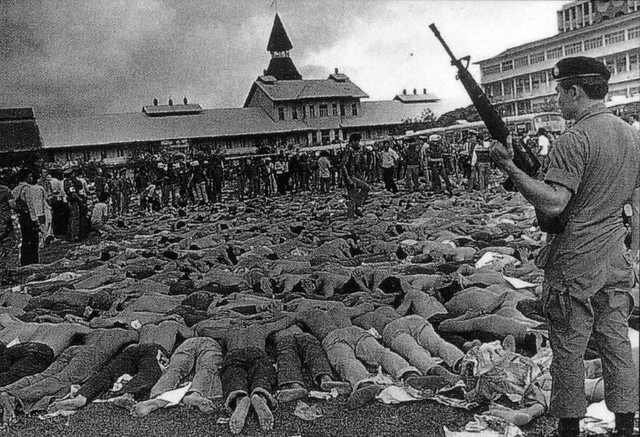

Student forced to lay down facing the ground during the student crackdown in Thammasat University, which later turned into a brutal massacre on 6 October 1976

Continue from Part I, Part II, and Part III

Teachers for Society

Nok Koon Jae (นกกุญแจ),Roi Et Rajabhat University

Affiliation: Independent, Members: 15

Chanin Yosboon wants to become a “teacher for society.” “My dream is to inform people to know their rights, and to know that their community is really important,” said Mr. Chanin, a 22-year-old Education major studying at Roi Et Rajabhat University.

He continued, “A career as a teacher is one of the careers that can inspire children to be interested in these kinds of issues.” Mr. Chanin is one of the founders of Nok Koon Jae, an independent student organization.

Nok Koon Jae means “key bird,” which is a type of pigeon, in Isaan, the regional dialect of Northeastern Thailand. Mr. Chanin chose this name intentionally: the bird symbolizes freedom, and the key unlocks the “secrets that society is hiding.” The majority of members study education, but these future teachers don’t restrict themselves to the confines of a classroom.

Nok Koon Jae helps different communities “fight for their rights” by bringing them together through joint activities, such as farming. In a recent water management project, fifteen members of Nok Koon Jae supported nearly 300 villagers at the nearby Chi River, an important water source in the Northeast.

“The real learning process happens when students have a chance to go to communities and learn,” said Mr. Chanin. He believes that Thailand’s educational system is not preparing future teachers for their job. Mr. Chanin remained relaxed and easygoing, yet all the while still managed to appear tall and upright from his seated position on the ground, and effectively convey his conviction in what he believed.

“I don’t think a lot of teachers truly understand society’s problems,” explained Mr. Chanin “because the government is typically the only source of information.”

Suprapha Khantiwong, a fellow Nok Koon Jae member and classmate who wants to teach so she can shape children’s decision-making abilities, agreed. “The knowledge we are taught inside the classroom is not enough,” Ms. Suprapha said, “The main problem of the Thai education system is that it teaches the opposite of reality.”

Although Ms. Suprapha seemed reserved because she didn’t speak often, the strength of her words would contrast with the quietness of her voice. It was clear that she was completely engaged in the conversation at hand and felt strongly about these topics.

Suprapha Khantiwong (left) and Chanin Yosboon have studied education together since freshmen year. As members of Nok Koon Jae, they work to build solidarity among Isaan communities.

Ms. Suprapha’s presence as a woman was particularly striking, even though not all of Nok Koon Jae was present, since women seem sparse in politically active student groups. Ms. Suprapha continued to explain how an example of this problem with the Thai education system is that, “The classroom teaches students that dams are good to hold water, and that when there is a drought, the dam will help people. But actually, if a dam is built, people in other areas won’t get water like they are supposed to.”

As Mr. Chanin and Ms. Suprapha see it, centralization is the main problem with the Thai education system. Having a singular standardized national curriculum creates a divide between what students learn in the classroom and the reality of their everyday lives.

Instead, Nok Koon Jae believes that villagers should have a say in creating community-based curriculum, so that traditional skills and local history won’t be lost. Decentralization of education, Ms. Suprapha and Mr. Chanin hope, will also encourage students to give back to their hometowns.

“As a teacher I want the future education system in Thailand to encourage students who graduate from universities to return to their hometowns and develop them,” Mr. Chanin said, “It is not necessary for them to continue being farmers; they just need to come back. They can bring back the knowledge they have learned.”

In their pursuit to promote justice, equality, and community rights, Nok Koon Jae will continue to live up to their group’s symbolic name of freedom. They refuse to be trapped by the confines of conventional education, and will instead choose to educate the future’s children as “teachers for society.” “In our role as teachers, we will be people who can actually help society,” said Mr. Chanin.

Invisible Generation

Naksueksa Kon Nueng (One Scholar) (นักศึกษาคนหนึ่ง), Ubon Ratchathani University

Affiliation: Independent, Members: 3

In a recent demonstration, a group of blindfolded and gagged students stood silently in their university’s food center. The striking signs that they carried read, “Where Are All the Scholars?”

These students are members of “Naksueksa Kon Nueng,” or “One Scholar,” a group that aims to call attention to the lack of students taking an active role in society and in the current political situation.

The group was founded less than a year ago. Chaiwit Kongnil, the independent group’s founder, firmly emphasized that, “Students should show that they have roles in society, and that they have opinions.” He continued, “Right now they are invisible, like they’re being blindfolded, like they’re being gagged. They should be visible.”

Despite the fact that his organization only has three members, he is working to recruit more members, and Mr. Chaiwit’s passion to his cause remains undeterred.

As to what is causing the absence of students’ voices in the current political situation, Mr. Chaiwit thinks aspects of Thai culture are contributing to their disengagement.

“Students are less interested in the political situation right now, because whenever there’s a problem—I think it’s a Thai thing, Thai people will just walk away,” said Mr. Chaiwit. “Thai people avoid problems and they hate confrontation. They hate to face problems. That’s why there’s less interest.”

He believes that the university’s environment also prevents the Thai younger generations from being politically active, since students are afraid to say what they think. “In the education system, we’ve been taught to not be so brave about coming up and standing up for our opinion,” Mr. Chaiwit expressed.

Naksueksa Kon Nueng student activists (One Scholar group) commemorating the student massacre in Thammasat University on 6 October 1976. The group gathered at the Ubon Ratchathani town square on 6 October 2013 with banners read “See things differently...you have to die? The fading memory” and “37 years passed since 6 October, many sacrificed their lives for their principles.” (taken from One Scholar Facebook Page)

Dr. Saowanne Alexander, a Sociolinguistics lecturer at Ubon Ratchathani University who studied in Bangkok and the United States, is among the few academics at her school who encourages her students to voice their opinion.

She echoed Mr. Chaiwit’s opinion that students are not pushed to have a critical perspective: “Thai people have been taught to be good students. What does it mean in the Thai system to be a good student? You listen to your teachers, you do what they say. You don't challenge them, and you don't ask too many questions. So, that mindset limits what you can say or think out loud,” she explained.

Dr. Alexander thinks that students in the Northeast are afraid to express their opinions because of the perceived consequences. She explained, “People can't be open, people can't be straightforward. Being too active can be a source of trouble for students too, because they can be targeted.”

When it came to talking about politics, Dr. Alexander was not afraid to call it as she saw it. Her straightforward manner was strikingly different from the indirect approach of avoiding problems Mr. Chaiwit had mentioned as a Thai cultural norm.

As a professor who tries to encourage her students’ opinions, it remains a tough work in progress. Dr. Alexander said, “It’s very frustrating for me, because I want my students to argue with me, to tell me what they want so that I can accommodate their needs and wants. But they don’t do that.”

Mr. Chaiwit used to be like other university students, trying to keep his head down and afraid to express his opinions. He was empowered to create his own independent student group after he participated in “Freedom Zone,” a non-profit organization that received funding from USAID. One of Freedom Zone’s goals is to get youth involved in talking about political and social issues, so as to best support democracy in Thailand.

“I was a member of the Student Union and worked for the university, but I thought that the activities of the university didn’t answer my goal. At about that time, USAID opened up something called the Freedom Zone,” Mr. Chaiwit explained. “It is an open space for students to learn how to become productive citizens.”

It was this event that inspired Mr. Chaiwit to found his organization. “The Thai older generation thinks the younger generations have no roles and no voice in the society. We formed this group to show them that we actually do have these roles in our society and roles in politics,” Mr. Chaiwit said.

Naksueksa Kon Nueng remains strong in their desire to encourage the invisible generation of students to step up and take part in removing their blindfolds and gags. “Students should be politically active, they should show themselves,” Mr. Chaiwit said with conviction. “They should have their own opinions. The political future should be created by us.”

Prachatai English is an independent, non-profit news outlet committed to covering underreported issues in Thailand, especially about democratization and human rights, despite pressure from the authorities. Your support will ensure that we stay a professional media source and be able to meet the challenges and deliver in-depth reporting.

• Simple steps to support Prachatai English

1. Bank transfer to account “โครงการหนังสือพิมพ์อินเทอร์เน็ต ประชาไท” or “Prachatai Online Newspaper” 091-0-21689-4, Krungthai Bank

2. Or, Transfer money via Paypal, to e-mail address: [email protected], please leave a comment on the transaction as “For Prachatai English”