UBON RATCHATHANI, THAILAND—The door of the Huahaew Irrigation Station is haphazardly ajar, its gray walls losing in a battle with rust. The station is vacant, its station engine silent. A horizontal water pipe emerges from the building’s grim face, ducking into the rocky earth, then resurfacing to slice across the landscape of dry, dusty clay. Eventually, the light gray cylinder turns into an open canal, which is buried in weeds just like the farmland it is meant to supply.

There are sixty other stations like this, built by the Royal Irrigation Department (RID) in an effort to expand farming in the area where the Mun River flows into the Mekong. They were constructed as a part of the Pak Mun Dam project, whose original purpose was to generate electricity, with the supplementary benefit of providing water to farmers in the dry season.

The Pak Mun Dam, built and operated by the Energy Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT), was expected to generate 136 MW of electricity and distribute river water to 64,000 acres in surrounding areas. These projections, however, were wildly exaggerated. The dam failed to meet its energy projection by 85%, and had such a negative impact on local communities that the World Commission on Dams concluded in its 2000 report that “if all the benefits and costs were adequately assessed, it is unlikely that the project would have been built.”

The dam devastated the livelihoods of fishermen and local fisheries, as the original 265 fish species in the river dwindled to 96 and family incomes dropped by sixty-four percent. Sustained protests forced the government to open the sluice gates four months a year.

Paijit Siwalak, leader at the Tai Baan Center, stands in an irrigation canal meant to receive water

Paijit Siwalak, leader at the Tai Baan Center, stands in an irrigation canal meant to receive water

from a nearby Pak Mun irrigation station built by the Royal Irrigation Department.

Many farmers in the Pak Mun area must grow hardy crops like cassava, or else risk low yields if irrigation stations break.

(Photo: Corona and Quintano)

At the face of such controversy, EGAT knew the Pak Mun Dam needed to meet its secondary purpose: irrigation.

Leaving the sluice gates closed for eight months, and especially during the dry season time, EGAT argued, would allow water behind the dam to rise to a level where it could be used for irrigation.

Natee Mapom, a public relations officer at EGAT, explained: “Many provinces are suffering from droughts and water shortages. Right now, there is not much water during the dry season, but the Pak Mun Dam helps reserve irrigation water for the people of Ubon Ratchathani.”

In an attempt to expand year-round farming, EGAT partnered with the Royal Irrigation Department (RID) in 2004 to transition the Pak Mun Dam into a primary source of water storage and installed a series of irrigation stations along the 80 kilometers between the dam and Ubon city.

“Many people believe these irrigation stations were built for political reasons,” says Mr. Paijit, a leader at the Thai Baan Center, which is resisting the Pak Mun Dam. “For these stations to work, the river water has to be at a certain level. It seems the government built them to justify leaving Pak Mun Dam’s sluice gates closed.”

Mr. Paijit argues that the push for irrigation is not only an attempt to salvage the Pak Mun Dam, but a continuation of a top-down agenda for agriculture. As a part of its irrigation expansion plans, the RID spent an average of 28.5 million baht ($873,467) alone on each irrigation station in the Pak Mun area. Such high investments in infrastructure and corresponding subsidies for out-of-season farming by the government agency have made the Thai Baan Center and other resistance groups wary.

“These [irrigation stations] are part of the government’s effort to change fishing people into farmers, and this is scary in a way,” says Mr. Paijit. He fears promotion of farming in the area by the government or EGAT draws attention away from the problems created by the dam.

Reliance on large-scale irrigation system also requires larger budgets for local TAOs (Tambon Administrative Organization). Paijit believes the costs for “water and station maintenance” will overwhelm TAO budgets.

The Khamkhuankaew TAO, which has jurisdiction over 16 villages in the Pak Mun area, currently pays 66% of the local farmers’ cost of water. Every year pressure increases for it to support agriculture in all seasons through the costly upkeep of irrigation stations.

According to one Khamkhuankaew official, the TAO has 200,000 ($6,667) baht in its budget for station maintenance, yet each time a station is fixed it costs 100,000. If stations have to be fixed more than twice, the TAO then has to divert funds from other projects in its budget. Unfortunately for the TAO and villagers, this happens more often than not.

“I am frustrated with the current irrigation system. My station is often broken, sometimes for as long as two months,” said Toei Phunchai, a rice farmer in the village of Khan Puai. “The area’s soil also can’t absorb the water well—it is too dry. Even if I had irrigation I would need to use a lot [of water], and it is still too much money.”

Paijit Siwalak, leader at the Tai Baan Center, stands above one of the Pak Mun Dam’s sluice gates.

The Center believes that hoping the gates for five years would prove to the government that the dam

should be decommissioned to restore the Mun River and the way of life of communities. (Photo: Corona and Quintano)

For Mr. Paijit, these problems stem from the EGAT’s failure to consider communities’ way of life when the dam and irrigation stations were built. The promotion of agriculture is another shortsighted solution from the government that does not acknowledge the area’s arid geography and the river-based knowledge of local people.

Instead of following unsustainable and inefficient irrigation projects, members of the Thai Baan Center are fighting to open the Pak Mun Dam’s sluice gates. Their confidence rides on the conviction that a fishing livelihood—especially for the case of Pak Mun people—holds equal or superior economic and cultural value to that of farming. If this is the case, the government’s irrigation scheme is missing the bigger picture.

EGAT, however, now places all its hopes on irrigation. “The importance of Pak Mun Dam in terms of electricity is no longer significant when compared to its role in irrigation. Irrigation now allows people to benefit from the Pak Mun Dam directly,” Mr. Natee stresses.

Mr. Santiparp, a professor of environmental science at Udornthani Ratchaphat University, however, does not think the benefits of irrigation can justify maintaining a dam that has cost so many villagers’ livelihoods.

“There’s already enough research from the past twenty years demonstrating that this dam is not needed, and it does not make sense for a dam built for producing electricity to be used for irrigation without having any strong reasons to do so,” he asserts.

Mr. Paijit describes the dynamic, “The irrigation system impacts some people if the dam is open, and impacts some people if it is closed. Fishing, however, impacts everyone. While irrigation can be provided if the gates are open—through technical conditions, floating water stations, etc.—it’s for fishing that we demand [EGAT] to open the gates.”

Paijit Siwalak, leader at the Tai Baan Center, stands in front of a floating irrigation station that was used by farmers before the Pak Mun Dam. Floating stations require minimal maintenance and function at any river level—

Paijit Siwalak, leader at the Tai Baan Center, stands in front of a floating irrigation station that was used by farmers before the Pak Mun Dam. Floating stations require minimal maintenance and function at any river level—

in stark contrast to the newer stations built by the Royal Irrigation Department.(Photo: Corona and Quintano)

In the past, villages irrigated through floating irrigation stations, which met the need of subsistence agriculture by adjusting to the level of the Mun River. Only after the Pak Mun Dam were such methods supplanted. As their fishing culture slipped away, the government’s stationary irrigation stations required reliance on the dam.

The Mun River had once been the villagers’ field—not for reaping crops of rice—but cultivating the region’s treasured freshwater fish. With this in mind, the Thai Baan Center is holding fast to two demands—for the Pak Mun Dam gates to be open for five years, and for families whose livelihoods were lost after the dam to receive 310,000 baht in compensation. It believes that the environmental and economic restoration resulting from these actions would outweigh the benefits of agriculture. These propositions—which were accepted by the previous Yingluck Administration—may or may not be adopted by the next prime minister.

Now, Mr. Paijit, like many in the Pak Mun community, continues to wait, haunted by one question: “If you can’t take a person’s land or rice, why was the government able to do it with water and fish?” he asks.

The Huahaew Irrigation Station waits as well, its pipes empty of water, the surrounding countryside barren and in want.

--------

Dani Corona and Allie Quintano study development issues with the CIEE Khon Kaen program. Dani studies Biology and Society at Cornell University, and Allie studies Informatics at Indiana University.

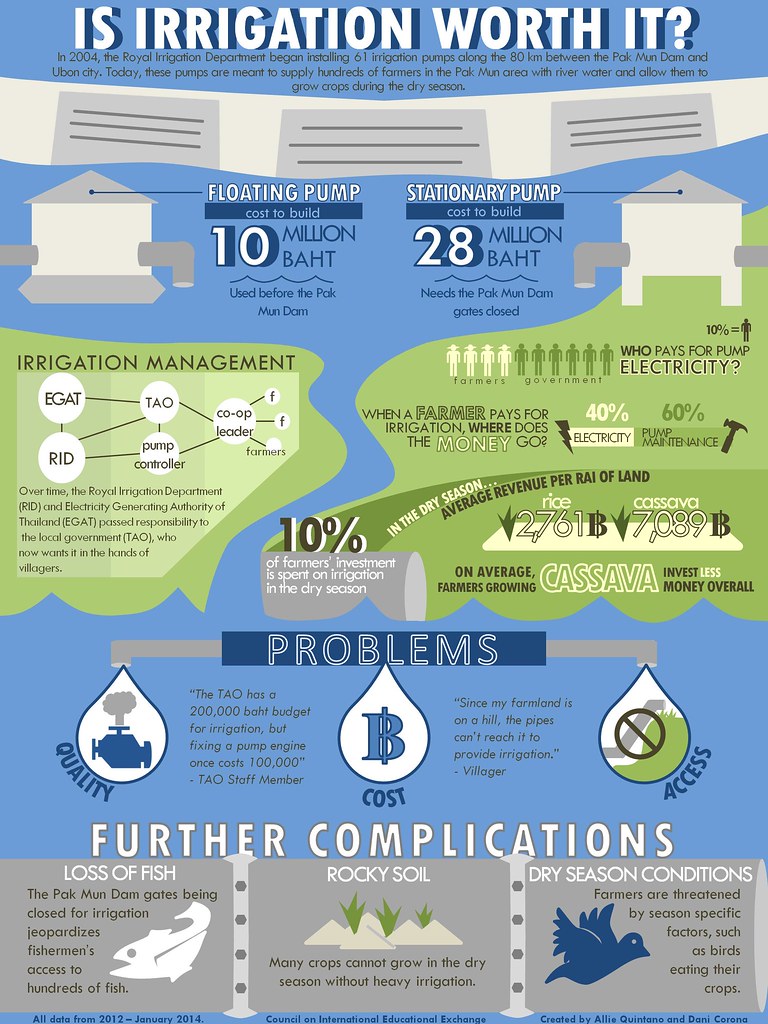

Should the Pak Mun Dam stay in commission to provide irrigation? An infographic explains the irrigation system farmers in the Pak Mun area use to grow dry season crops—but with many difficulties and questionable success.